A major winter storm is expected to bring heavy snow, strong winds, and coastal flooding across the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast that may cause impossible travel conditions and power outages. Blizzard conditions are possible along coastal areas from the DelMarVa Peninsula through southeastern New England. Wet weather and strong winds return to the Pacific Northwest and north-central California. Read More >

History of

Russell Pfost*, Pablo Santos, & Robert Garcia |

Florida has a long storied history beginning with the indigenous Indians encountering the Spanish explorers in the 16th century. St. Augustine is its oldest city with over 440 years since its founding in 1565. Even so, many of the cities and towns in Florida are very new, especially in the central and south sections. Habitation by people in the central and south counties of Florida was uncomfortable and unhealthy before the advent of air conditioning and mosquito control.

Miami is perhaps the best known city in Florida, and it has experienced boom and bust throughout its short history. It has known the Spanish-American War, Henry Flagler and his railroad, the Roaring Twenties, the Depression, World War II, segregation and civil unrest in the 50s and 60s, the Cuban missile crisis and the Mariel Boat Lift, and the tremendous influx of Latin American immigrants in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. The character of Miami has changed dramatically through all this time, and today it is a vibrant, multi-cultural city with a pervasive Latin flavor of its many Latin American residents.

Contents

- Indigenous Indians and the Spanish Explorers

- Fort Dallas, the Seminole Wars, and the War Between the States

- The Signal Service and the Weather Bureau at Jupiter

- The Weather Bureau Moves to Miami

- Hurricane Disasters of 1926 and 1928

- Growing Aviation Needs

- Labor Day Hurricane of 1935

- Hurricane Forecasting Comes to Miami with Grady Norton

- The National Hurricane Center and Gordon Dunn

- Weather Bureau Becomes The National Weather Service

- Hurricane Andrew and Doppler Radar

- NWS Modernization

- Computer Advances

- Hurricane Katrina and Max Mayfield

- Recent Times

- List of Past and Present Weather Leaders in Miami Area

Indigenous Indians and the Spanish Explorers

The following narrative is taken from the Historical Museum of Southern Florida's web site:

| "Hundreds of years earlier, before Christopher Columbus (Cristobal Colon) discovered the New World, the Tequesta Indians lived here. The first to appreciate South Florida's mild climate, the Tequestans lived simply. Abundant food supplied from the land and sea made agricultural activities unnecessary. In 1566, the Tequesta settlement was visited by Pedro Menendez de Aviles, his men, and Brother Francisco Villareal. One year earlier, Menendez had founded St. Augustine, the oldest city in the United States, and now came to South Florida to establish a Jesuit mission. Within a few years it was abandoned and another attempt to Christianize the Tequestans was not made until 1743. That effort was also short-lived. During the more than two centuries that Florida was controlled by Spain, the Tequestans and other Prehistoric Indians of Florida were decimated by European diseases and warfare. The lands they vacated attracted people from several of the Creek tribes in Georgia and Alabama who had entered Florida as early as 1704. Collectively, they became known as Seminoles, and during the nineteenth century they would engage in a series of bloody wars against the United States partly to defend their right to live in Florida. After the conclusion of the Third Seminole War in 1858, the few hundred Indians remaining in the state lived in the Everglades. The first permanent white settlers in the Miami area arrived in the early 1800s. During the decades that followed, a wide variety of individuals left their mark on the history of this area. In the 1830s, statesman Richard Fitzpatrick from South Carolina (later William English) operated, with slave labor, a successful plantation on the Miami River. He cultivated sugar cane, bananas, corn and tropical fruit. Fitzpatrick was driven from his plantation by the Seminole Indians. Major William S. Harney, in command at Fort Dallas which was located on Fitzpatrick's Plantation on the north bank of the Miami River, led several raids against the Indians during the Second Seminole War (1835-1842)." |

It must be mentioned that the first good weather records in South Florida were taken at Key West, probably America's richest city between 1828 and the mid 1850s due to the salvaging of many ship wrecks on the treacherous reefs off the Florida Keys. Temperature records with many breaks begin in 1829 and some rainfall measurements are available beginning in the 1850s. These records continue even through the War Between the States years due to the early occupation of Key West by federal troops.

Fort Dallas (established 1837) was one of a series of forts built by the U.S. Government during the Seminole Wars from 1816-1818, 1835-1842, and 1855-1858. The first weather observations taken in what is now the Miami area were at Fort Dallas during the Second Seminole War. The first observer at Fort Dallas was Assistant Surgeon I.H. Baldwin, U.S. Army, beginning in October 1839. Temperature records, with many breaks, are available from 1839 to 1855 from the Fort Dallas site near present day 2nd Avenue SE and 4th Street SE. Temperatures and rainfall are available from the Fort Dallas site from 1855 to 1858 with many breaks.

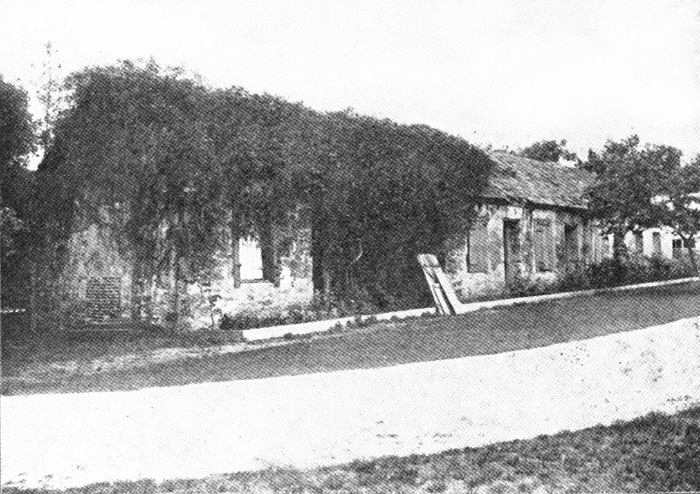

Fort Dallas Slave Quarters, in 1904 and today, now located in Lummus Park, downtown Miami

U.S. Army Assistant Surgeons at Fort Dallas kept meteorological records during the Second and Third Seminole Wars

from the Battle of Olustee, Fla. (Baker County),

1864, web page

The War Between the States (1861-65) had little effect on South Florida outside of Key West, because of the very few residents and the lack of any strategic reason for Confederates to defend the area. Fort Dallas likely remained in Union hands throughout the war and probably served as a base for ships participating in the naval blockade of the Confederacy. After the war, refugees and desperadoes were often residents at Fort Dallas, including Judah P. Benjamin, Confederate statesman, who used the fort as a hideout during his successful flight through Cuba and back to his native Great Britain in 1865. In 1866 all-but-abandoned Fort Dallas was occupied by Yankee carpetbaggers W.H. Hunt and W.H.Gleason and their families, who later became reconstruction Radical Republican politicians from then sparsely populated Dade County. Gleason's political escapades (The Gleason Gang) during Reconstruction in Tallahassee are well documented. Hunt later became the first cooperative weather observer in the Biscayne community (see below).

The Signal Service and the Weather Bureau at Jupiter

In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a joint resolution of Congress establishing a weather service within the Army. Observations were taken at 22 sites by the Army Signal Corps and the word 'forecast' was first used. An Army Signal Corps weather observation site was established in November 1871, at Punta Rassa (near Fort Myers) on the west coast and at Jupiter Inlet in July, 1879, on the east coast. (More information from a national perspective on the Signal Service era of the National Weather Service can be found at the NWS history web site.) The Jupiter Signal Service station is the ancestor of today's Miami National Weather Service offices.

Jupiter Lighthouse complex, 1908. Weather Bureau is the rightmost building.

Courtesy Lynn Lasseter Drake collectionEarly meteorological observations (under the direction of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington) were also taken in Dade County at 'Biscayne', which was a small settlement of a dozen or so homesteads in the present-day Miami Shores area. The first observer in 1870 was W. H. Hunt, previously mentioned Yankee carpetbagger and radical Republican state senator from Dade and Brevard counties, which at that time adjoined each other. He turned over the observing duties in 1872 to Ephraim Sturtevant, a fellow carpetbagger and native of Connecticut, graduate of Yale, who had lived and taught in Ohio before moving to post-bellum Florida in 1870. He was also the father of Julia Tuttle (the 'Mother' of Miami), who was born in Cleveland, Ohio. You can see the records entered by Sturtevant in early September of 1878 when a strong hurricane moved north-south across South Florida just west of present-day Miami/Fort Lauderdale/West Palm Beach. In 1880, the Biscayne temperature and rainfall records ended as the Sturtevants returned to Ohio (Sturtevant died in 1881). The other settlers of Biscayne either moved on (Gleason and his family moved to Eau Gallie, a town he founded in Brevard County), some going south to Fort Dallas or other Dade County communities, or passed away, and the town fell into disrepair. Julia Tuttle moved to the old Fort Dallas in 1891 (a few years after her husband died) and converted it to a homestead.

In 1890, at the request of President Benjamin Harrison, Congress created the Weather Bureau within the Department of Agriculture. On July 1, 1891, the meteorological mission of the Signal Service was officially transferred to the Weather Bureau. The Jupiter Signal Service station therefore became the Jupiter Weather Bureau with Alexander J. Mitchell as the Official-in-Charge (Mitchell was later a long term Official-in-Charge of the Jacksonville Weather Bureau) followed in 1894 by James W. Cronk. On December 29, 1894, the State of Florida experienced its worst freeze since 1835 and another severe freeze occurred February 8-9, 1895. The only South Florida meteorological record of those two freezes was at Jupiter, where the temperature dropped to 24 on December 29, and to 27 on February 9. Partially as a result of those two severe freezes which were reportedly much less severe near Biscayne Bay (local legend contends that Julia Tuttle sent an orange blossom to show that the freeze had not affected the Miami area), Henry Flagler decided to extend his railroad south from West Palm Beach to the northern shore of the Miami River and build a luxury hotel there.

While the Jupiter Weather Bureau was keeping accurate records of meteorological conditions for (at that time) northern Dade County, unfortunately no meteorological records were kept in the Miami area again until September, 1895, when a new station was established at Lemon City (possibly as a result of those two freezes farther north in Florida). Lemon City was a town located near the present day intersection of NE 2nd Avenue and 60th Street. From Larry Wiggins' study entitled "The Birth of Miami" available on the Historical Museum of Southern Florida's web site:

| The Miami area, in the years leading up to the railroad's arrival, was better known as "Biscayne Bay Country." The only overland transportation to the area was by a hack (or stagecoach) line that ran from Lantana on them southern end of Lake Worth to Lemon City on Biscayne Bay. The few published accounts from that period describe the area as a wilderness that held much promise. Lying five miles north of the Miami River, Lemon City could boast of only fifteen buildings in 1893. However, many homesteaders had settled on land up to five miles away from the core of the settlements. One of these buildings was a new hotel that could accommodate twenty-five to thirty guests. Two miles south were several people living in Buena Vista. "Cocoanut Grove" (as it was spelled then) sat ... south of the Miami River; it contained twenty-eight buildings "of a very neat and tasteful character," two large stores doing an "immense business," and a hotel run by Charles and Isabella Peacock. Cutler, eight miles south of Cocoanut Grove, also contained a few settlers. |

The Lemon City site (first observer was the Rev. Charles W. Kimball, who only lasted one month, followed by Edmund Lindsay (E.L.) White, who later administered Julia Tuttle's estate after she died in 1898), recorded temperatures and rainfall sporadically for five years from September 1895 to April 1900 (with a break in July 1897 and another break from June through August 1899). It was during this time that the Biscayne Bay area experienced the first "boom" in anticipation of the Flagler railroad. The town of Miami was set out on land previously owned by Julia Tuttle and William Brickell on the north and south sides of the Miami River, respectively. The railroad tracks reached Lemon City on April 3, 1896 and the new town of Miami (7 miles to the south) only 4 days later on April 7.

The Weather Bureau Moves to Miami

As the town of Miami rapidly began to develop, the economic importance of spreading information about the mild climate undoubtedly influenced the establishment of a cooperative temperature and rainfall recording site at 131 SE 1st Street, now near the heart of downtown, in December, 1900 (observer was the Rev. E.V. Blackman, Methodist minister). The Rev. Blackman also received telegrams with weather warnings from the Weather Bureau in Washington, DC, which he posted at the door of the Post Office. Instruments remained there until June, 1911 (the Jupiter Weather Bureau under Official-in-Charge at that time H. P. Hardin was closed in May 1911) when the city's first official Weather Bureau Office (WBO) was established.

The following narrative is taken from Local Climatological Summary for 1949:

| In June, 1911, a first order Weather Bureau station was opened in the Bank of Bay Biscayne Building, at the northwest corner of Miami Avenue and Flagler Street. Instruments were exposed on the roof. Height, in feet above ground and above roof, respectively, were for the anemometer, 72 and 44; rain gage, 32 and 4; thermometers 37 and 9. The exposure was excellent. In August, 1914, the instruments were moved to the roof of the Federal Building, on the corner of Northeast First Avenue and First Street. The heights were, anemometer, 79 and 19; rain gage 64 and 4; thermometers, 71 and 11. Exposures were excellent until November, 1916, when the erection of an eight story building 110 feet south of the instruments reduced the velocity of south winds by 25% or more. In October, 1919, a six story building was erected about 100 feet to the northeast, affecting the velocity of winds from that direction. In November, 1925, a 17 story building was erected east of the instruments resulting in the recording of only a small percentage of east winds. This building was torn down to the fifth floor in December, 1926, greatly improving the exposure. In July, 1927, the wind instruments were moved to the roof of the Seybold Building (picture circa 1920s, picture today), near the center of the block bounded by Miami and Northeast First Avenues and Flagler and Northeast First Streets. Height of the anemometer was 168 and 31 feet. ... In July, 1929, the rain gage and thermometers were moved to the Seybold Building. Elevations were, rain gage, 117 and 4; thermometers, 124 and 11. The exposure was excellent until 1939, when a 17 story building 1-1/2 blocks east reduced the velocity of winds from that direction. In January, 1943, the instruments were moved to the roof of the Congress Building, 111 Northeast Second Avenue. Heights were, anemometer, 249 and 19; rain gage, 234 and 4; thermometers 242 and 12. The exposure was excellent except for a slight effect on southwest winds caused by a 17 story building about 250 feet to the southwest. In June, 1948, the instruments were moved to the roof of the east penthouse of the Vocational Education Building (later called Lindsey Hopkins Building), 1410 Northeast Second Avenue. Heights, anemometer 229 and 45; rain gage, 188 and 4; thermometers, 193 and 9. The exposure is excellent except apparently there is some diminution of rainfall catch during high winds. |

This renewed interest in weather in Miami corresponds well with the national demand for weather information. In 1898, President William McKinley ordered the Weather Bureau to establish a hurricane warning network. Around 1900, the Weather Bureau began to experiment with kites to measure temperature, relative humidity, and winds in the upper atmosphere. In 1909, the Weather Bureau began to use balloons for upper air information, a method still in use today. The advent of aviation changed the Weather Bureau substantially. In 1926, the Air Commerce Act directed the Weather Bureau to provide for weather service to civilian aviation. By the early 1930s kites were becoming a hazard to airplanes in flight, causing kite observations to be discontinued in 1931.

Richard Gray and the Hurricane Disasters of 1926 and 1928

The first Official-in-Charge (OIC) of the newly established WBO in 1911 was Richard Gray (1874-1960), who transferred from the old Army Signal Service weather office at Jupiter, Florida. He had one assistant, C.B. Moseley, Jr. Gray's legacy includes his now famous actions during the devastating category 4 1926 hurricane which struck Miami September 17-18, killing more than 100 people and causing millions of dollars in damage. In the first part of the 20th century, warnings for hurricanes were often late and inadequate without modern satellite pictures, computer models, and surface observations. Although storm warnings were issued by the

Damage in downtown Miami after the 1926 hurricane

WBO at noon on the 17th, hurricane warnings were only issued as the barometer was falling and winds were rising at 11 PM local time, after most Miamians were asleep. You can read a description of what the WBO staff were doing in the office that night in parts 1, 2, and 3 of the official observation forms for September 1926. Some reports have Gray running through the streets of Miami shouting the warning in an effort to warn the sleeping population of the imminent danger before the worst winds began.. At 1 AM local time, 2 hours after the warnings were issued, winds reached hurricane force along the coast. Gray also apparently returned to the streets during the passage of the eye of the storm (the calm lasted about 35 minutes) to warn residents venturing outside that the lull would not last and that the wind would return from the opposite direction with greater force that before. Gray's narrative (parts 1926-a, 1926-b, and map) of the 1926 hurricane was included in the American Meteorological Society's publication Monthly Weather Review. [The National Weather Service sponsors a State of Florida historical marker commemorating the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 which stands at the corner of NE 1st Avenue and 1st Street, downtown Miami. The marker was dedicated on September 18, 2007, the 81st anniversary of the hurricane.] Only two years later, the category 4 Okeechobee hurricane would kill over 2,500 people primarily in a huge storm surge from Lake Okeechobee into the lakeside communities from South Bay to Belle Glade and Pahokee.

The Weather Bureau Responds to Growing Aviation Needs

A direct result of the 1926 Air Commerce Act, but not in operation until September 4, 1929, the Miami Weather Bureau Airport Station was first established at 11229 Northwest 42nd Avenue (near today's East 10th Avenue and 56th Street in Hialeah) at Miami Municipal Airport. Official psychrometric observations were not taken at that location until September 1, 1930. Dry and wet bulb thermometers, mounted on standard whirling apparatus, were exposed in an instrument shelter, over a sod covered plot, bounded 20 feet on the east and 30 feet on the west by paved roads. The location was about 13 miles northwest of central Miami. Biscayne Bay was about 7 miles to the east and Everglades about three miles west. Pibals (pilot balloons) began at the site on November 1, 1930, and rawinsonde observations (raobs) began on July 12, 1939, showing the importance of upper air observations to aviation. Ralph L. Higgs was the Junior Meteorologist in charge of the station. For many years, 1929 through 1975, the City of Miami had a WBO downtown and a WBAS at the airport.

The Labor Day Hurricane Disaster of 1935

In early 1935, Ernest Carson became the MIC of the Miami WBO (Click here for a newspaper picture of Gray, Higgs, and Carson in 1941). In mid 1935, tropical cyclone forecasting was reorganized from one centralized operation in Washington to four tropical cyclone forecasting offices (San Juan, Jacksonville, New Orleans, and Washington) based on geographic areas of responsibility, along with increased funding ($80,000). Hurricane forecasters Grady Norton (senior) and Gordon Dunn (junior) worked at the Jacksonville office. The new setup was severely tested within a few short weeks. The 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, a very small but viciously intense category 5 storm, devastated the middle Florida Keys killing hundreds of World War I veterans who were working on the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) Overseas Highway project as well as scores of local residents (click the link to see a pdf file of an incomplete map of cremations and burials of the victims from the House of Representatives hearings in 1936 - the map shows how far the victims were scattered across Florida Bay due to the violence of the hurricane, some all the way to the mainland). The reaction to the Labor Day disaster was loud and contentious. Congress appropriated even more money ($128,000) in late 1935 to improve observations and reports for tropical cyclones.

Grady Norton Leads a New National Hurricane Office in Miami

In 1940, the Weather Bureau was moved from the Department of Agriculture to the Department of Commerce, showing the increased importance of aviation weather. In 1943, when the downtown weather instruments were moved to the roof of the Congress Building in downtown Miami, the primary hurricane forecast office was moved from Jacksonville to Miami as well. Grady Norton became the Meteorologist-in-Charge of the new office which established a joint hurricane warning service with the Weather Bureau, Air Corps, and Navy. Norton served as MIC of the Miami office until his death in 1954. During World War II, the first radar, a WSR-3 radar, was installed at Miami. The first airplane flights into hurricanes occurred during the decade of the 1940s as well, heralding the beginning of the hurricane research effort. Over at the WBAS, the Miami Municipal Airport site was purchased by the U.S. Navy in 1942, and on July 31, 1942 the WBAS moved to (then) Pan American Field, site of today's Miami International Airport, 5010 Northwest 36th Street, about 5-1/2 miles northwest of central Miami. Ralph Higgs transferred to San Juan, PR, in 1942, and Earl S. Hanlon became the Assistant Meteorologist in charge of the WBAS, followed by Paul H. Kutschenreuter in 1943 (Kutschenreuter went on to later become Deputy Director of the National Weather Service). The thermometers were exposed about 5-1/2 feet above the ground, 100 feet north of the main terminal building, over a sodded area bounded by asphalt drives 20 feet to the east, west, and south. Beginning in February, 1949, the readings were obtained from a telepsychrometer, exposed in the same location, over a sodded area of 1000 square feet, surrounded by a paved parking area. Biscayne Bay was 6 miles to the east; the Everglades area was 3-1/2 miles to the west. Wilmer L. (Tommy) Thompson became the WBAS Official-in-Charge in 1947.From 1947 through 1950, South Florida endured very active hurricane seasons. Two hurricanes struck South Florida in 1947, the first very large Cape Verde storm made landfall near Fort Lauderdale on the morning of September 17 as a category 4 with maximum reported one-minute sustained wind of 155 mph at the Hillsboro Lighthouse. It moved west very slowly, around 10 mph, and finally exited the state near Naples late that night. The second hurricane to strike South Florida came from the northwest Caribbean to make landfall near Cape Sable on October 11. This hurricane produced tremendous flooding from torrential rainfall as well as at least two tornadoes. Two more hurricanes struck South Florida in 1948, on very similar paths that originated in the Caribbean, crossed western Cuba and the Florida keys, and moved across the extreme south part of the Florida peninsula from southwest to northeast. The first struck on Sept. 21-22 and the second came on October 5. In 1949, only one hurricane struck South Florida, but it did great damage to the Delray Beach/Palm Beach area of South Florida where it made landfall on August 26 before moving across the north part of Lake Okeechobee toward the Tampa Bay area. In 1950, a very small but intense hurricane named King made landfall near Miami Beach just before midnight on October 17 and the eye passed directly over Miami. Hurricane King caused a damage path that was only 7 to 10 miles wide that, according to Weather Bureau MIC Grady Norton, looked like a large tornado damage path.

The National Hurricane Center and Gordon Dunn

In 1948, the WBO moved to the Lindsey Hopkins Building (referred to as the Vocational Education Building earlier) at 1410 NE 2nd Avenue. Grady Norton (1894-1954) died from a stroke in 1954 after working a 12 hour shift at the Weather Bureau forecasting Hurricane Hazel. Walter Davis became the Acting MIC until a new MIC could be selected. The 1954 hurricane season produced three storms that affected the densely populated Middle Atlantic and New England states (Hurricanes Carol, Edna, and Hazel), forcing increased attention from politicians in Washington. Congress then appropriated increased money for the Weather Bureau in 1955 that included a new radar network, an improved hurricane warning network, and hurricane research (The National Hurricane Research Project). Gordon Dunn, at that time MIC of the WBO in Chicago, Illinois, was eventually selected as the new MIC for the Miami WBO. In 1955, the Miami WBO was designated the primary national Hurricane Center but hurricane forecast responsibility remained assigned to San Juan, Miami, Boston, New Orleans, and Washington, DC offices based on geographical areas.On February 28, 1957, the WBAS (airport station) was moved 1 mile south and 0.4 mile east to the CAA&WB Building located on the 20th St. side of Miami International Airport. Walter Davis became the Chief Airport Meteorologist at the WBAS in 1962. On July 1, 1958, the WBO/NHC (city office) moved to the Aviation Building at 3240 NW 27th Avenue while WBAS (airport) records continued at the Miami International Airport. The WSR-57 network radar was installed at the Aviation Building on June 26, 1959. Temperature records for the downtown site ended with this move. It must be mentioned that prior to the establishment of the airport site, the location of thermometers on top of tall buildings in downtown Miami made the accuracy of temperature records for the period 1914-1958 very suspect, especially in radiational cooling or inversion situations. Even the airport records, because of proximity to asphalt roads, parking areas, and runways, must be considered somewhat suspect until winter 1977, when instruments were moved near the west end of the runways at Miami International Airport.

On December 23, 1964, the Miami WBO/NHC moved again, this time to the campus of the University of Miami and the Computer Building, 1365 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables. The WBAS remained at the airport, but came under the supervision of the WBO/NHC rather than a separate office. In 1966, the WBO/NHC was officially designated the National Hurricane Center (NHC) with primary hurricane forecast responsibility for the entire Atlantic basin. Official Miami weather records continued to be taken at the Miami International Airport. From 1967 until administrative division in 1984 the National Hurricane Center/National Weather Service histories are the same (numerous articles have been written about NHC history and published in AMS journals, see references below). Gordon Dunn (1905-1994) retired at the end of the 1967 hurricane season, succeeded by Dr. Robert H. Simpson.

The Weather Bureau becomes The National Weather Service

In 1970, the Weather Bureau became the National Weather Service (NWS). After the 1973 hurricane season, Dr. Simpson retired and was succeeded by Dr. Neil Frank. The WBAS at Miami International Airport was finally contracted out by the NWS in 1975, and personnel either transferred to NHC or were employed by the contract observer. On January 19, 1977, flurries of snow were observed all across peninsular Florida, including the metro West Palm Beach/Fort Lauderdale/Miami areas extending as far south as Homestead. This established a new record for the farthest south observance of snow in Florida, besting the previous record set in 1899 when trace amounts fell as far south as Fort Myers on the Gulf coast to Fort Pierce on the Atlantic coast. In June 1979, the NHC moved from the University of Miami to the 6th floor of Gables One Tower, an office building across from the university on Dixie Highway. At this time, computers were already being used for forecast modeling purposes at NWS national headquarters in Washington and, to a lesser extent, at field offices. Even so, it wasn't until the early 1980s that the Automation of Field Operations Services (AFOS) system was installed at Miami as part of the first nationwide operational computer and communications system for the NWS.

Miami Weather Forecast Office and the National Hurricane Center on the FIU campus, 1995-present

Administrative changes in 1984 resulted in the separation of the research and operational groups of NHC as well as the operational division of the state oriented Miami Weather Service Forecast Office (WSFO) from the international scope of the tropical cyclone forecast program. WSFO Miami assumed all forecast and warning responsibility for Florida east of the Apalachicola River under longtime hurricane forecaster and Louisiana native Paul Hebert as its new MIC and the Southern Region of the NWS. The tropical cyclone program was administratively reassigned under the National Meteorological Center (NMC) in Washington, DC as a national center called the Tropical Prediction Center (TPC). The tropical cyclone research effort was moved to a new Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) building on Virginia Key (a good history of the U.S. hurricane research effort can be read in Dorst's article, see reference below). In 1987, Dr. Frank retired and accepted a position in broadcast meteorology in Houston, Texas. Dr. Bob Sheets succeeded Dr. Frank as the Director of TPC.

Hurricane Andrew and New Doppler Radar

Category 5 Hurricane Andrew struck south Dade County on August 23-24, 1992. The NWS WSR-57 radar on top of the office building blew down that night. The devastation across south Dade County was severe, making Andrew (then) the costliest hurricane (since eclipsed by devastating Hurricane Katrina in 2005 with more than 50 billion dollars in damages) in American history with about 26.5 billion dollars in damages. The new Doppler radar, the WSR-88D, was installed ahead of schedule due to Andrew in April 1993, at a location near the Miami Metro Zoo. The WSR-88D was commissioned on April 20, 1995. In May 1995, the TPC/WSFO moved into a new hurricane resistant building in the extreme southwest corner of the Florida International University campus close to the intersection of the Florida Turnpike Extension and the Tamiami Trail (U.S. 41). On the TPC side, Dr. Sheets retired in 1995 and was succeeded near the beginning of the 1995 tropical cyclone season by hurricane researcher Dr. Bob Burpee. Dr. Burpee was succeeded in 1997 as Director by Jerry Jarrell. Jerry led the National Hurricane Center through Hurricane Georges and category 5 killer Hurricane Mitch in 1998.On May 12, 1997, an F1 tornado moved through downtown Miami, witnessed by thousands as it happened and then millions more as the pictures made national headlines. The tornado was detected and warned for in advance using the WSR-88D Doppler radar. This event, and the Groundhog Day tornadoes in February of 1998, were wakeup calls for South Florida residents that hurricanes are not the only severe weather threat for our region.

NWS Modernization

In the early 1990s, the NWS embarked on a massive modernization and restructuring plan, which included not only upgrading all the old WSR-57 radars to the new 'Next Generation Warning Radar' (NEXRAD) WSR-88D Doppler radars, but also upgrading computer equipment and reorganizing forecast offices away from state boundaries to radar coverage oriented county warning areas (CWAs). Under the CWA concept, the State of Florida's forecasts and warnings changed from two WSFOs with forecast and warning responsibility (Birmingham, Alabama, and Miami, west and east of the Apalachicola respectively), and a number of smaller WSOs with warning responsibility only (Mobile, Tallahassee, Jacksonville, Daytona Beach, Orlando, Tampa, Fort Myers, West Palm Beach, and Key West) to seven Weather Forecast Offices (WFOs) (Mobile, Tallahassee, Jacksonville, Tampa Bay, Melbourne, Miami, and Key West) with warning and forecast responsibility based on radar coverage. In August 1998, the new Advanced Weather Interactive Processing System (AWIPS) was delivered and accepted at the Miami NEXRAD WSFO (NWSFO) as an eventual replacement for the aging AFOS system. On November 15, 1999, the CWA concept with seven WFOs was officially started and the old Miami WSFO became the WFO for mainland South Florida. The Miami WFO assumed warning and forecast responsibility for seven counties (Glades, Hendry, Collier, Palm Beach, Broward, Miami-Dade, and mainland Monroe) and their coastal waters out to 50 nautical miles as well as Lake Okeechobee. The Miami WFO retained state responsibility for the temperature and precipitation tables and the state forecast product.Computers continue to be a huge part of weather forecasting and warning. As computer technology improves each year, the many calculations required to predict atmospheric motions become easier and faster. Better and better models will be developed in the next several years to provide more accurate and timely forecasts. Automation due to computers is rapidly taking over such duties as broadcasting forecasts and warnings on NOAA Weather Radio, taking routine surface observations (ASOS - Automation of surface observing systems), and upper air balloon observations.

Computers Advance Weather Forecast CapabilitiesPaul Hebert retired in June 1998, ending a 39 year career in weather. Russell (Rusty) Pfost, then science officer at the NWS office in Jackson, Mississippi, was selected as the new MIC for WSFO Miami in August 1998. In 2002, the Miami WFO began issuing gridded weather forecasts using a Graphical Forecast Editor as well as the traditional text forecasts. Gridded forecasts from WFOs across the country are now being combined into a National Digital Forecast Database (NDFD). In 2005, additional radar information from the FAA Terminal Doppler Weather Radars (TDWR) for Palm Beach International Airport began flowing into AWIPS, providing redundant radar coverage for the Treasure Coast and Lake Okeechobee and TDWR radar data from Fort Lauderdale International Airport and Miami International Airport was added in spring 2008. In 2007, a GPS rawinsonde replacement system was installed across the country, including WFO Miami, which greatly improved the accuracy and timeliness of upper atmosphere data for operational forecast model input.

Hurricane Katrina and Max Mayfield

At NHC, Jerry Jarrell retired in 2000, and was succeeded by veteran hurricane forecaster Max Mayfield. Since 2000, TPC/NHC has begun issuing graphical and probabilistic tropical cyclone forecasts in addition to text products, greatly expanding the amount of information available to decision makers everywhere. For the 2003 hurricane season, forecasts for tropical cyclones were extended from three to five days. Recent studies have shown that the five day track forecast is as accurate as the three day track forecast was 15 years ago. Max Mayfield was Director during the record-breaking hurricane seasons of 2004 and 2005, including Hurricane Katrina which devastated the Louisiana and Mississippi Gulf coasts. The NWS, led by Max Mayfield and TPC, provided proactive early notification of political and emergency management officials in Louisiana and Mississippi. The proactive information enabled emergency managers to initiate mass evacuation plans and was credited with saving many lives from Katrina's devastating storm surge and damaging winds and rain. Max became a trusted face and voice of the National Hurricane Center during the experiences of the trying 2004 and 2005 seasons. Max Mayfield retired in January, 2007 and was succeeded briefly by NWS Southern Region Director Bill Proenza until June 2007 when he was reassigned. Also in 2007, TPC began an experimental Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook as a companion to the traditional text product. The GTWO has proven to be extremely useful and popular, and more graphical products are on the horizon as well as probabilistic products and maps, including probabilistic storm surge. A new and comprehensive summary of NHC's history since Dr. Bob Sheet's article in 1990 has just been published. You can see it here: https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/rappaport-et-al-wf2009.pdf.

In 2004 and 2005, South Florida also experienced a very active hurricane period. Three hurricanes (category 4 Charley on August 13 near Punta Gorda,category 2 Frances on Sept. 5 near Stuart, and category 3 Jeanne on Sept. 25 also near Stuart) made landfall on the south part of the peninsula in 2004 and two (category 1 Katrina on August 25 near Hallandale Beach and category 3 Wilma on October 24 near Everglades City) made landfall on the south part of the peninsula in 2005. While the 2006-2009 hurricane seasons were relatively quiet for mainland South Florida (except for the torrential rains from Tropical Storm Fay in 2008), it is likely that the next several years will continue to be quite active for tropical cyclones across South Florida given the global circulation patterns that are now in place across the planet.

On January 25, 2008, then WFO Houston/Galveston MIC Bill Read was selected as the new Director of TPC. Ironically, Bill Read's first hurricane season as director included Hurricane Ike, which inundated the northwest Gulf of America coastline including the Houston/Galveston metro area with a devastating storm surge. In 2011, Bill Read's last hurricane season as NHC Director, the northeast was impacted by Hurricane Irene which resulted in catastrophic floods across that region of the country. Once again, the NWS provided outstanding advance warning of the impending disaster from Ike, led by Bill Read and TPC. Also under Read's leadership, the name "Tropical Prediction Center" or TPC (which never quite caught on) was retired and the far more widely known and accepted name "National Hurricane Center" or NHC returned to the office.

At NHC, Director Bill Read retired in June 2012 after four and a half years leading the nation’s hurricane program, and was succeeded by Dr. Rick Knabb who had previously been the science officer at NHC before serving a stint as deputy director of the Central Pacific Hurricane Center in Honolulu and a short period as the tropical weather expert at The Weather Channel. Dr. Knabb’s first hurricane season on the job included Hurricane Sandy, an October hurricane that swept across Jamaica, Cuba and the Bahamas before becoming very large and restrengthening off the east coast of the United States, finally turning northwest and making landfall in New Jersey on October 29 as a post-tropical cyclone. Because of Sandy’s enormous size, the storm caused a catastrophic storm surge along the heavily populated New Jersey and New York coastlines, resulting in 72 direct deaths in the U.S. (most due to storm surge) and over $50 billion in damages (second costliest cyclone to hit the U.S. since 1900). But the biggest controversy concerning Sandy was its transition to a post-tropical cyclone in the hours before landfall and the problem of best communicating information about the storm through landfall and even beyond. Once Sandy was declared post-tropical less than 3 hours before landfall in New Jersey, tropical cyclone watches and warnings ended and responsibility for warnings and information switched to local NWS forecast offices along the Atlantic seaboard. This proved to be confusing to some and disruptive to the flow and understanding of critical information despite NHC excellent forecast. Changes implemented for the 2013 season broadened warning definitions and will enable the centralized flow of information from NHC to continue regardless of internal structure of storms. Future changes will also include separate storm surge watches and warnings as well.Decision support services for emergency management, law enforcement, and government are becoming more and more important. During the week of February 1-7, 2010, WFO Miami-South Florida meteorologists were deployed to the joint operations center in support of the 2010 Super Bowl at Dolphin Stadium. Gulf coast WFOs from Brownsville to Miami provided real time support for the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill disaster back in 2010. Over the past several years WFO Miami has provided onsite support for emergency management agencies working on events such as Tropical Storm Isaac, the Fort Lauderdale Air Sea Show and NASCAR at Homestead Speedway among others. On site weather support will continue to become even more critical for hazardous substance incidents and water issues as time moves forward.

At WFO Miami-South Florida, MIC Rusty Pfost retired in June 2010 after a 32 year career with the NWS, and Dr. Pablo Santos, WFO Miami-South Florida Science and Operations Officer, was selected as the new Meteorologist-in-Charge. In 2023, Dr. Santos transferred to NHC to lead the Technology & Science Branch. Donal Harrigan and Robert Molleda are serving tours as acting Meteorologist-in-Charge.

R. W. Gray (1911-1935)U.S. Signal Service, Jupiter, Fla.

Sgt. Henry Pennywitt (1888)

Pvt. M. W. Lichty (1888-1891)

Weather Bureau, Jupiter, Fla.

A. J. Mitchell (1891-1894)

P. J. O'Brien (1894)

J. W. Cronk (1894-1899)

C. J. Doherty (1899)

H. P. Hardin (1899-1911)

Weather Bureau, Miami, Fla.

Weather Bureau Office (WBO)/City Office/National Hurricane Center (1966- )

National Weather Service, National Hurricane Center, Miami, Fla.

Dr. R. H. Simpson (1970-1973)

Dr. N. M. Frank (1974-1987)

National Weather Service, Miami, Fla.

National Hurricane Center/Tropical Prediction Center

Dr. N. M. Frank (1974-1987)

Dr. R. C. Sheets (1987-1995)

Dr. R. W. Burpee (1995-1997)

J. D. Jarrell (1997-2000)

B. M. Mayfield (2000-2007)

X. W. Proenza (2007)

W. L. Read (2008-2012)

Dr. R. Knabb (2012-2019)K. Graham (2019-2022)

Dr. M. Brennan (2023-Present)

Weather Service Forecast Office (WSFO) / Weather Forecast Office (WFO)

P. J. Hebert (1984-1998)

R. L. Pfost (1998-2010)

Dr. P. Santos (2010- 2023)

Donal Harrigan/Robert Molleda (acting 2023-present)

Former NHC Directors

Here is a picture of some of the past directors of the National Hurricane Center at a past Hurricane Conference in New Orleans, LA. From left, Brian Jarvinen (former NHC storm surge program leader and SLOSH model expert), Max Mayfield (Director, 2000-2007), Jerry Jarrell (Director, 1998-2000), Billy Wagner (emeritus Monroe County, Florida, Director of Emergency Management), the late Robert Burpee (Director, 1995-1997), Robert Sheets (Director, 1987-1995), Neil Frank (Director, 1973-1987), Robert Simpson (Director, 1967-1973), and the late Herbert Saffir (engineer and creator of the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale). The past hurricane center directors not pictured are the late Grady Norton (MIC of WBO Miami, 1943-1954), the late Gordon Dunn (Director, 1966-1967, MIC of WBO Miami 1954-1966), Bill Proenza (2007), Bill Read (Director, 2008-2012), and Richard Knabb (Director, 2012-2019).

SELECTED REFERENCES

Burpee, R.W., 1988: Grady Norton: Hurricane Forecaster and Communicator Extraordinaire. Wea. Fcstg., 3, pp. 247-254.

Burpee, R.W., 1989: Gordon E. Dunn: Preeminent Forecaster of Midlatitude Storms and Tropical Cyclones. Wea. Fcstg., 4, pp. 573-584.

Dorst, N.M., 2007: The Nationa Hurricane Research Project. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 88, pp. 1566-1588.

Douglas, M.S., 1958: Hurricane. Rinehart and Company, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Gray, R.W., Jr., interview with J. Watters, 1972(?). Reichelt Oral History Program, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida.

Pfost, R. L., 2003: Reassessing the Impact of Two Historical Florida Hurricanes. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 84, pp.1367-1372.

Rappaport, E.N. et al., 2009: Advances and Challenges at the National Hurricane Center. Wea. Fcstg., 24, pp. 395-419.

Scott, P., 2006: Hemingway's Hurricane. International Marine / McGraw-Hill, Camden, ME.

Sheets, R.C., 1990: The National Hurricane Center—Past, Present, and Future. Wea. Fcstg., 5, pp. 185-232.

Whitnah, D.R., 1961: A History of the United States Weather Bureau. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL.

The Miami Daily News, numerous articles.

The Miami Herald, numerous articles.

Miami Public Library, List of Obituaries.

Top Ten U.S. Natural Disasters (in terms of death toll)

1. Galveston (Texas) Hurricane, 1900, estimated 8,000 deaths

2. Great Okeechobee Hurricane in Florida, 1928, estimated 2,500-plus

3. Johnstown (Pennsylvania) Flood, 1889, estimated 2,200-plus

4. Cheniere Caminada (Louisiana) Hurricane, 1893, 2,000-plus

5. Hurricane Katrina (Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida), 2005, estimated 1,836-plus6. Sea Island (South Carolina-Georgia) Hurricane, 1893, 1,000-2,000

7. San Francisco Earthquake, 1906, 700-800

8. Great New England Hurricane, 1938, estimated 700

9. Savannah (Georgia-South Carolina) Hurricane, 1881, 700

10. Tri-State Tornado in Missouri, Illinois and Indiana, 1925, 695

* (interviews also with Gil Clark, Paul Hebert, Jim Lushine, Max Mayfield, Bob Burpee, Alvin Samet, Suzanne Cawn, articles by Don Gaby, and the South Florida Historical Society)